It’s quite possible I finished four books this month; two may have been started in January, but four in a month is a recent record for me in finishing.

Both of these books I bought as part of my interest in westerns and #western106. While both are in the range of western genres, they could not be more different, all of which seemed interesting when I placed them side by side and noticed the similar range of colors in the cover.

I bought Stephen King’s The Gunslinger for 25 centers from the Pine Arizona Senior Center Thrift store, picking it up to read while on my 6 weeks of travel.

As a teen I ripped through Stephen King novels- Carrie, The Shining, Salem’s Lot Cujo, Firestarter, The Dead Zone (maybe my all time favorite), The Stand (no maybe it was this one), and then Different Seasons, the four stories, three of which became movies (Shawshank Redemption, The Stand, Apt Pupil). I thought he jumped his own shark with Pet Cemetery and even more lamely with From a Buick 8.

King’s characters were loners, misfits, outsiders who had life changing / or revenge gaining experiences brushed into the supernatural or gothic/horror, and all wrapped in a lot of cultural references I grew up in.

Reading Stephen King is like slicing through soft butter. It tastes good, it’s easy cutting.

It’s been maybe 25 years since I read one of King’s novels, but the writing of The Gunslinger was like slipping on a broken in pair of jeans. It was ok, but seemed a bit just trying to be too clever with allusions to the world we know as lost or parallel (“ka”), and this western post apocalyptic landscape roamed by his Gunslinger on a mission, the troubled Good Character (the Last One Left) chasing after– wait for it– a Man in Black.

It’s the first of a seven book series, and it felt pretty much like watching Lost… you felt like you’ve get some understanding of the world, then its turned inside out, and you are told to tune in for the next episode.

Probably the better writing parts to me where the flashbacks.

King was much better at creating the environments of the towns of Main he grew up in; his Gunslinger’s walk across the desert was pretty much a trek across the California Mohave desert, over the mountains, to the sea- a western path. Because this is a landscape I have lived in, traveled, gotten lost and thirsty in, I feel King’s descriptions more based on stuff looked up, than having lived in the dry southwest.

So while reading Stephen King is like cutting through that soft butter, reading Cormac McCarthy is like fighting your way through a thick stand of the desert shrub known as cat’s claw:

Acacia Bush, or Cat’s Claw, photo from New Mexico State University “Medicinal Plants of the Southwest”

I met this beast in my first two weeks after moving to Arizona in August 1987 – what I chose to do in August shows my desert ignorance, but I headed out to the Superstition Wilderness area east of Phoenix and set up to hike up Siphon Draw.

What looks like from a distance to someone who grew up in Maryland as a route through some soft green shrubs– is a pathless maze of cross hatched branches of cat’s claw, named for the spikes on the branches. Making your way through this stuff leaves you looking like this:

flickr photo shared by cogdogblog under a Creative Commons ( BY ) license

But once you fight your way through, take your blood scratches or get smarter about picking your routes, well then you might be rewarded

Pillars at the top of the Superstition Mountains, my own pre-digital photo, taken before 1996 (date it was scanned)

That’s what reading McCarthy is like- working your way through cat’s claw. You have to work at at. And if you just take it literally, you miss it all. I think.

I read at least All The Pretty Horses and The Crossing, but really got turned more into a McCarthy-ite with No Country For Old Men. The one I really really loved, and no one seems to see it like me, was The Road. Most readers get focused on the terror and horror of the post apocalyptic future painted by McCarthy, that to me, was just the background setting for a beautiful love story of a father and son, and a testimonial to the hope of the human spirit. I love that book.

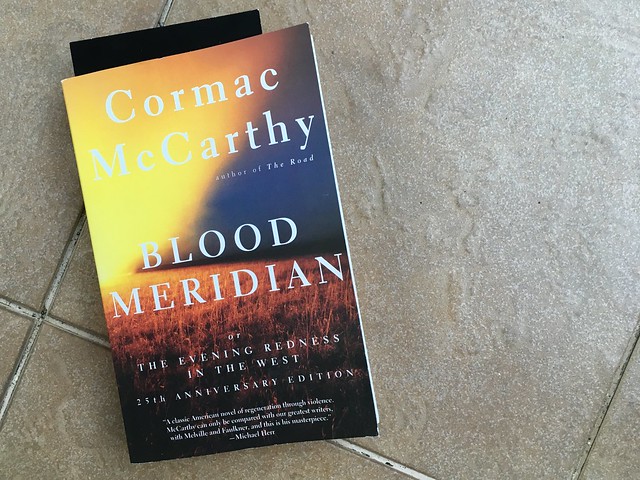

So when I was plotting the idea of a Western106 version of DS106, many well-read folks like Jim Groom and Scott Leslie told me that I had to read Blood Meridian, that it was maybe McCarthy’s most intense novel. I knew what kind of intensity they were hinting at. I picked up my copy at a bookstore in San Juan, Puerto Rico while I was there in February, and somehow read the thorny pack of cat’s claw in about 3 weeks.

That’s not to say I am ready to give a high level summary or even explanation. You can get the full range of reactions in places like Goodreads where many of the reviews describe it from “unquestionably the most violent novel I’ve ever read. It’s also one of the best.” “Spilled…emptied…wrung out…soul-ripped…that pretty accurately sums up my emotional composition after finishing this singular work of art. ” and somewhere is the dismissive “I don’t get it, the kid was a dumb asshole, the writing is so hard to read…”

And it is hard to read. It is not a single style, like King. The writing is as much about the harsh land of the west as it is OF that same land. It can flow along clearly like a mountain stream, it can tumble like a boulder slide in a monsoon storm, it can be vast stretches of nothingness… there is the long dialogue without declaring who is talking or punctuation, so you have to really stick close to it’s flow.

flickr photo shared by cogdogblog under a Creative Commons ( BY ) license

But that’s the essence of McCarthy’s writing to me- it is exactly like that harsh, broken desert, with far vistas of golden colors, with crags, crevices, snakes, cacti, razor rocks, in between. It’s a land that dwarfs you and your ideas, your aspirations, your concepts of fairness, and pretty much does not care about the doings of humans.

The land does not give a **** about you. It’s stronger than you, it has stood there eons longer than you will.

And that is woven through Blood Meridian, this meridian itself, the inexact margins of US and Mexico cultures, histories around 1850, the violence of climate, of people, this is the true west- not the fanciful one of cliche westerns where Good always Triumphs over Bad. And all of this, and the violence that rides from page 1 to page 351 is the reflection of us as humans. Not a full reflection, but as the Judge describes, denying this essence is denying who we are, and what our history has been.

It’s not a condoning of the violence of human nature, it is an acceptance or an understanding of it.

Anyhow, I don’t have a comprehensive summary to share, as my head is still spinning from the end, and I avoided all those blog posts that hinted at what a mindf*** the end was, and provided warnings of spoilers. I should do the same.

The arcs of the characters in Blood Meridian shift and shape like desert clouds. You might think the Kid is a central hero, but his character fades to non-existence in the middle third of the book, and we get more focus on Glanton and the Judge, and all the violent acts they do are or done to them. It’s not even clear why any of the others in this troop are even associated with this outfit; the implication is they are all rejects of some sort from whatever life they had before. Glanton and the Judge grow to be almost superhuman, the Judge more so.

But you do kind of end up rooting for The Kid, which to me says there is more darkness to his story than is apparent. Some writers suggest The Kid is responsible for abusing young girls in the travels, it’s never explicitly stated. He is set to face the Judge, and yep, that happens.

The Judge is a character of shifting gigantic proportions. What he does and knows (the languages he speaks, the way he finds the paths, the scientific inquiry) expands without limit. People marvel in his first appearance at the revival tent how The Judge disrupted it with no basis with false accusations, like he is just some malicious manipulator who lives to mess with people. But I see it as just a hedged bet by the judge, that knowing what he does of people in general, the chances were likely that Reverend Greene was guilty of evil acts– that the Judge knew he had a chance of being right in his accusations without even needing that knowledge. He sees the heart of Man.

And I do not even think we find out what kind of judge is he– or even if he was part of a legal system. He seems a different kind of judge– The Judge in capital letters, the Judge of Humanity? I do not buy into the idea that he is Satan; he does evil acts, he is evil, but he is also our own reflection.

I also found it interesting how McCarthy does not paint the Indians all in the same stereotypical swath that most Westerns do. There are the Delaware, who work with the US mob as scouts/translators; there are Apache, Comanche, Yuma, Salado, and more that I am forgetting– some are marauding and kill in the most violent way. We never know their backstory; the implication to me is that they are no doing this as their way, but it is a return act for al the violence that the white settler, and maybe even spanish/Mexican settlers did to them.

And what exactly is this band of Americans doing was they proceed west, paralleling the country boundary meridian? They get these contracts to kill Indians, but they get so indiscriminate in their targets that they are more or less killing anyone in their path, until they end up on the other end of the chase. Like the Gunslinger, they too are headed in the same map direction, west west and more west. I had some fun in seeing that the meridian at the time led them through southern Arizona, Tubac and Tucson, then the deadly parts where they take over the Colorado River crossing near Yuma (there is a metaphor in there I bet).

If I started highlighting or noting things in this book, the pages would be covered with mad marks. I did start maybe halfway in dog earring pages that had something of interest. I wonder if I can figure out in hindsight why I marked some pages.

The first was where the ex-priest Tobin is telling The Kid about his first encounter with the Judge. The Kid mentions that he first ran into him in Nacogdoches (the tent revival thing). It is telling when McCarthy writes:

Tobin smiled. Every man in the company claims to have encountered that soothysouled rascal in some other place.

This almost suggests that supernatural powers of the Judge (or whatever he represents), that he has appearances in people’s lives, almost like he is a Pied Piper.

But my dog ear mark points to Tobin’s tale of he being part of a group that more or less finds the judge sitting alone on a rock in the wilderness. He describes the Judge’s rifle (in that way where like a desert illusion McCarthy zooms in and swirls around one small detail):

He had with him that selfsame rifle you see him with now, all mounted in german silver and the name he’d give it set with silver wire under the checkpiece in latin: Et In Arcadia Ego. A reference to the lethal in it. Common enough for a man to name his gun. I’ve heard Sweetlips and Hark From the Tombs and every sort of lady’s name. His is the first and only ever I seen with an inscription from the classics.

Other writers might mention that the judge carries an ornate gun laced with silver. And this is one of those things in reading McCarthy you can just push on through the acacia to get to the next bit, or you can jump out and explore.

I was curious about Et In Arcadia Ego and landed in an article by Tracy Twyman- The Real Meaning of “Et in Arcadia Ego” and the Underground Stream:

“Et in Arcadia Ego …” — These words may have first appeared in a painting by Il Guercino (c.1618) of the same name. Throughout the Renaissance, this phrase was used as a sort of code word for “the underground stream,” an invisible college of kindred souls who secretly shared their esoteric knowledge with one another, passing it around Europe via a network of secret societies and mystery schools, often utilizing its arcane symbolism in works of art and literature.

Twyman writes that the latin is for “I am in Arcadia” where the “I” is suggested to mean death, and Arcadia is paradise. In Renaissance paintings, this underground stream is often associated with images of skulls (see how often bones and skulls figure in Blood Meridian?)

There is much more to it that the article parses out, but this idea of duality (the Kid vs the Judge) Death being a part of Paradise, that we as humans have an underground stream, is well, the guts of the book.

The next mark in my book was shortly after, as McCarthy is making the judge grow larger, another extremely detailed of the Judge cataloging in his journal notes and drawings an inordinate amount of detail from an Indian ruin- tracing pottery fragment textures, sketching/shading details in his book. He is working like a scientist, like a curator– then when he is done, the Judge tosses the artifacts into the fire!

Then he sat with his hands cupped into his lap and he seemed satisfied with the world, as if his counsel had been sought at its creation

Later in the tale the judge talks about this idea of making an inventory of all that is unknown in his journal, that doing so gives him power over it.

Whatever exists, he said. Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent.

In the earlier section I noted, a man Webster fears being cataloged as such, asks the Judge not to sketch him (something like some civilizations not wanting a camera to steal their soul?).

The judge riddles this man with the suggestion that as a man he cannot escape being cataloged in someone’s book:

The judge smiled, Whether in my book or not, everyman is tabernacled in every other and he exchange and so on in an endless complexity of being and witness to the uttermost edge of the world.

The judge, being explicit in his notebook taking is suggesting (?) that it is human nature that we constantly are adding each other to our own internal journals?

We then get the judge’s tale of the harnessmaster, and the expression about raising children by putting them in pits with wild dogs.

If God meant to interfere in the degeneracy of mankind would he have not done so by now? Wolves cull themselves, man. What other creature could? And is the race of man not more predacious yet? The way of the world is to bloom and to flower and die but in the affairs of men there is no waning and the noon of his expression signals the onset of night. His spirit is exhausted at the peak of his achievement. His meridian is at once his darkening and the evening of the day.

My emphasis in bold for the reference to meridian, which to me, is the one in us, not some line on the map between the US and Mexico. That we have this nature of war in us; later the judge pronounces when one of the menu suggests that the bible calls war evil.

It makes no difference what men think of war, said the judge. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner. That is the way it was and will be, That way and not some other way.

War, the violence, in the judge’s explanation, is part of man, that there is no meridian we can put between it and something else.

This has winded on long enough. Even in going back to my dog-eared pages, and seeing more connections that jump across the book has been valuable. Do not believe that I “understand” this book. Yet. I am more experiencing it, and can easily see doing a re-read in the future. I can not forsee re-reading The Gunslinger.

But yes the book ending. The discussion boards are rampant with attempts to explain it, to understand the vaguely described ending. The Judge and the Kid. Are they one? Are they really opposites? We are tempted to have some affinity for the Kid, we want to sense that he has some sense of morality. But he has been a participant in all the same violence that the rest of the gang has done; his role is not described in the middle fo the book, but he is no virtuous soul either. Who is? The idea of “good” vs “evil” as separate entities is too simple. We all both, not either, with our own swirling meridian.

I don’t think we are meant to know exactly what happened in the “jakes” nor does it matter. I think it is all the horrible things that people have guessed it, it is not one act of violence that horrified the men who peeked in, but all of them.

There is something too about the metaphor of the bear that was shot; the attempts of man to tame, to change the powerful parts of nature, and to turn it into something of an amusement. It’s how we treat our planet, overpowering it into a dancing bear that we just kill for no reason.

There’s not too much pondering about The Gunslinger; it was a fine tale and I enjoyed following it. I will send the book back to the thrift store. But I am not seeing much more to it.

flickr photo shared by cogdogblog under a Creative Commons ( BY ) license

On the other hand I’m still reeling a bit with Blood Meridian. Each time I think of it I have more questions. This one is staying on my shelf.

Top / Featured Image: My own photo of two books I purchased with my own money. I read them both in the interest of #western106 though neither are stereotypical. I was struck by the similar color schemes in their cover.

The photo is mine on flickr https://flickr.com/photos/cogdog/24887778133 shared under a Creative Commons (BY) license

Two down, two to go! Poor ol Stephen King having to compete with Blood Meridian! Great job parsing your way through McCarthy’s masterpiece. It is also my favorite novel. Jim Groom said he was going to read it, too. I wonder if that happened?

McCarthy is sort of like Goya in his Capriccios. http://www.smb.museum/en/exhibitions/detail/am-rande-der-vernunft.html

He really is some kind of brilliantly mad Surrealist where you have to read with all your cultural feelers out, your soul open, your ears open to the violent compelling music. I love that bit of Underground Stream research you did–that adds a Borgesian layer, an echo of Eco.

Wonderful read–thank you for your intense thinking and writing in this post.