Because my current work now is centered in open education, and coming off of Open Education Week, I was swimming much in conversations, workshops about Open Pedagogy (often as acronym OEP).

I am not here to offer Yet Another Definition (check one of the best resources). I welcome this as moving beyond Open Education as “stuff” (courses, resources, textbooks) but the practice of teaching.

I am here to state that it’s hardly new. It did not come about with the internet or from Pressbooks. And if you speak with more primary school teachers (like a podcast I did with two of them recently, check it out), the practices of inquiry-based learning that is novel in higher education is every day stuff for elementary level teachers.

Comments in some sessions were emphasizing the benefits of students as teachers and also contributing to publications is key practices.

My memories fired off in realizing I had experienced these as a student… in the 1980s. And I am confident you can find examples done, forgotten that go much further back.

This is no criticism of what people are discovering now. It is more an awareness of rather innovative practices I experienced in my education. If they had buzzwords for what they were doing, we did not hear of them.

I Have to Teach WHAT to My Fellow Math Students? (1980)

Let’s hop in the time machine to maybe, 1980, in my 10th grade math (or maybe it was Geometry) class at Milford Mill High School in Baltimore. I had a young, young teacher (he had pimples), maybe it was his first or second year teaching, blessed with the probably unfortunate name of “Mr Pitz.” To a math nerd he was anything but “the pits.”

I believe he recognized me and maybe three other kids were well ahead of the class in understanding. One day Mr. Pitz pulled us aside to give us a special project to work on while he taught the rest of the class. We had to research, learn ourselves, and teach to him and the rest of the class a topic that maybe still bends my mind.

The geometry we are all taught is Euclidean, based on what we learn that parallel lines never intersect. You know, two points make a line and it goes forever off the edge of your paper to the end of the universe. Non-Euclidean Geometry is based on that not being true, that parallel lines can intersect.

The place where maybe it makes sense is thinking about lines on a sphere, like longitude.

It hurts the head, right? Especially 10th grade ones. I cannot remember the specific assignment, but we had a few weeks to learn enough of this, including some proofs and equations, to teach a class on it. I am not sure what resources we had to work with (no one had heard of the internet), probably some books Mr Pitz provided and whatever else we could find in our library.

Having a Wikipedia article helps! The importance of this alternative geometry is a lot about changing the way we understand knowledge, and gets into philosophy:

The discovery of the non-Euclidean geometries had a ripple effect which went far beyond the boundaries of mathematics and science. The philosopher Immanuel Kant‘s treatment of human knowledge had a special role for geometry. It was his prime example of synthetic a priori knowledge; not derived from the senses nor deduced through logic — our knowledge of space was a truth that we were born with….

Non-Euclidean geometry is an example of a scientific revolution in the history of science, in which mathematicians and scientists changed the way they viewed their subjects. Some geometers called Lobachevsky the “Copernicus of Geometry” due to the revolutionary character of his work.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-Euclidean_geometry

I remember less about this topic than this unexpected way which class was done. Given a challenge like this fed some young minds which might have been bored in math class.

Kudos to you Mr Pitz, not only this, but for 11th grade when you taught my first class in computer programming- where we got on busses to go to the school on the other side of town that had a VAX computer for processing our punch cards.

That experience alone was integral to where I am today.

Contributing to a Textbook (1984)

Perhaps the most commonly activity associated with Open Pedagogy is asking students to research and write chapters in an open textbook, almost always Pressbooks. I have no quarrels with this, and it was the podcast with University of Alberta student Nicole who cited this experience in a course with Verena Roberts, that propelled her into more acts of open education.

I experienced this myself as an undergraduate students in a Structural Geology course at the University of Maryland, circa 1984. I had just transferred there from another program and knew little about the program or faculty. Our professor was from outside the University- he worked for NASA a Goddard Space Flight Center.

As it turns out, he was thus unconventional. I had no idea how important Paul D. Lowman was as a scientist, he was just my professors. Only later do I discover he was one of the original scientists at Goddard, maybe the first geologist hired at NASA:

Lowman helped plan the early Apollo missions and later became involved in analyzing lunar samples and interpreting data from the Apollo 15 and Apollo 16 missions. He did early “comparative planetology,” researching what new information from the Moon and Mars could tell us about Earth. He is considered to be the father of Earth orbital photography which led to multispectral imaging of Earth and Landsat satellite imagery.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_D._Lowman

Structural Geology is about faults, and folds, and landforms that shape the earth we see and walk around on. He spoke early about using satellites to see from far above the earth the landforms we were studying. Later Dr Lowman introduced a project (without mention of Open Pedagogy) where were each given a photo of a Landsat satellite image of a key structural geology feature, with a name and location. Our task was to use the LIbrary to research as much background geology we could discover. Our research would be used to write a summary of the image in a book that would be published.

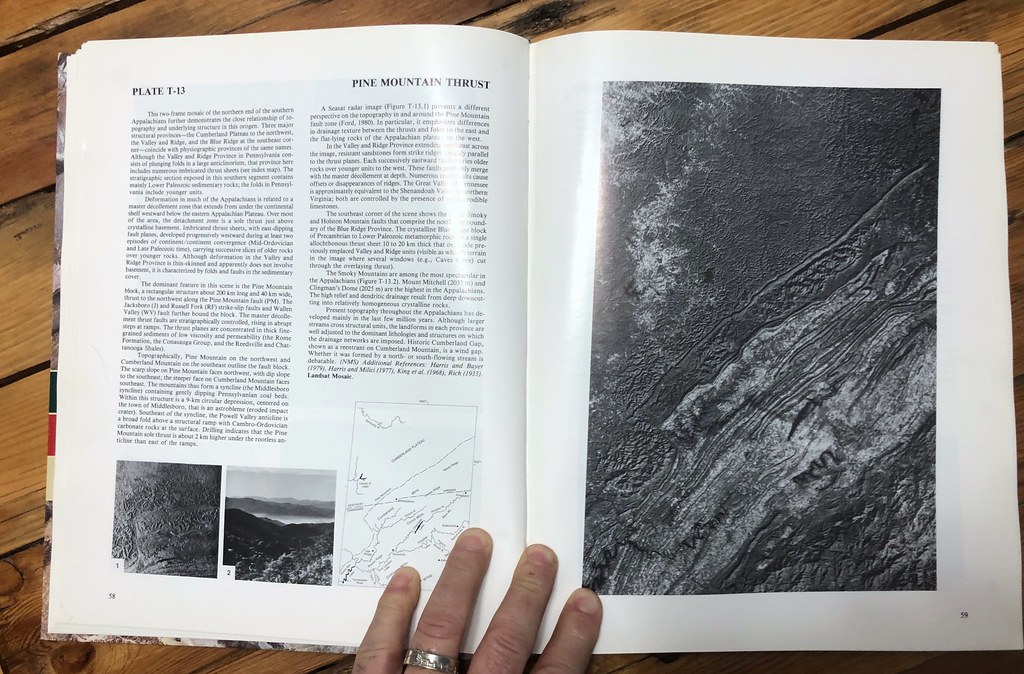

I don’t have my paper, and I likely did not keep the photo image (maybe we had to return) but I can always remember that I was assigned the Pine Mountain Thrust, demonstrating the classic Valley and Ridge geology of the Appalachian mountains. It’s down there in the junction of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia.

I cannot say much about how much of my writing made it into the final version, but I have a copy of the very book it was published in, Geomorphology From Space.

A web version was once published on a NASA site, but all I can find is a clone sitting on a site at the Geographical and Geological Sciences, University of Adam Mickiewicz, Poland. It is so old it has no license (I would think as a NASA project it was public domain).

Plate T-13 has the image I was assigned and the description of this Landsat scene:

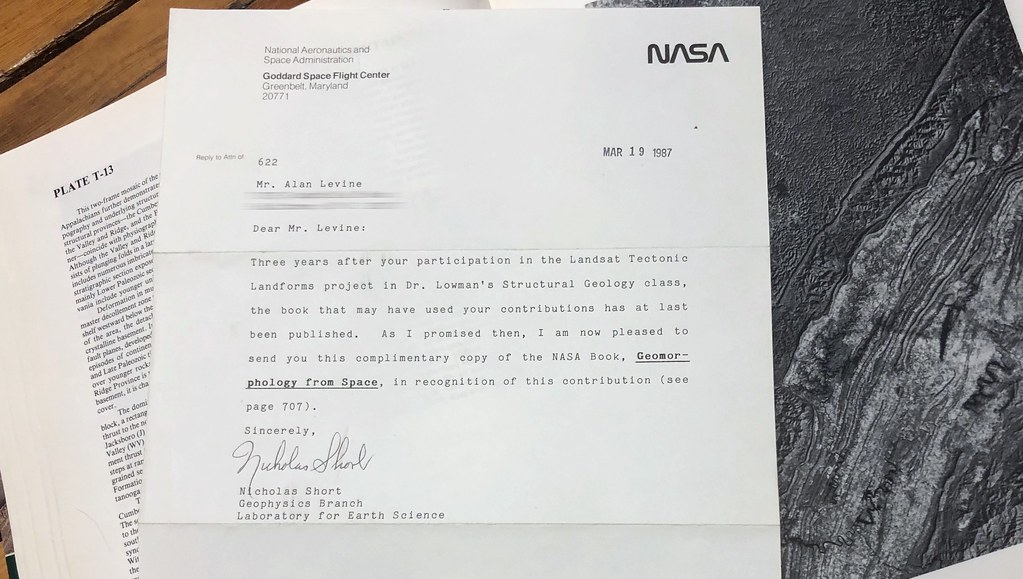

How many words there were mine? I cannot even guess as I tossed most of my assignments (hah, does that make this a disposable non-disposable assignment?). Inside the book is a letter to me from the primary author, Nicholas Short:

The letter dated March 19, 1987, aka 35 years ago, reads:

Dear Mr Levine

Three years after your participation in the Landsat Tectonic Project in Dr. Lowman’s Structural Geology class, the book that may have used your contributions has at last been published. As I promised then, I am pleased to send you this complimentary copy of the NASA Book, Geomorphology From Space, in recognition of this contribution (see page 707).

Sincerely,

Nicholas Short

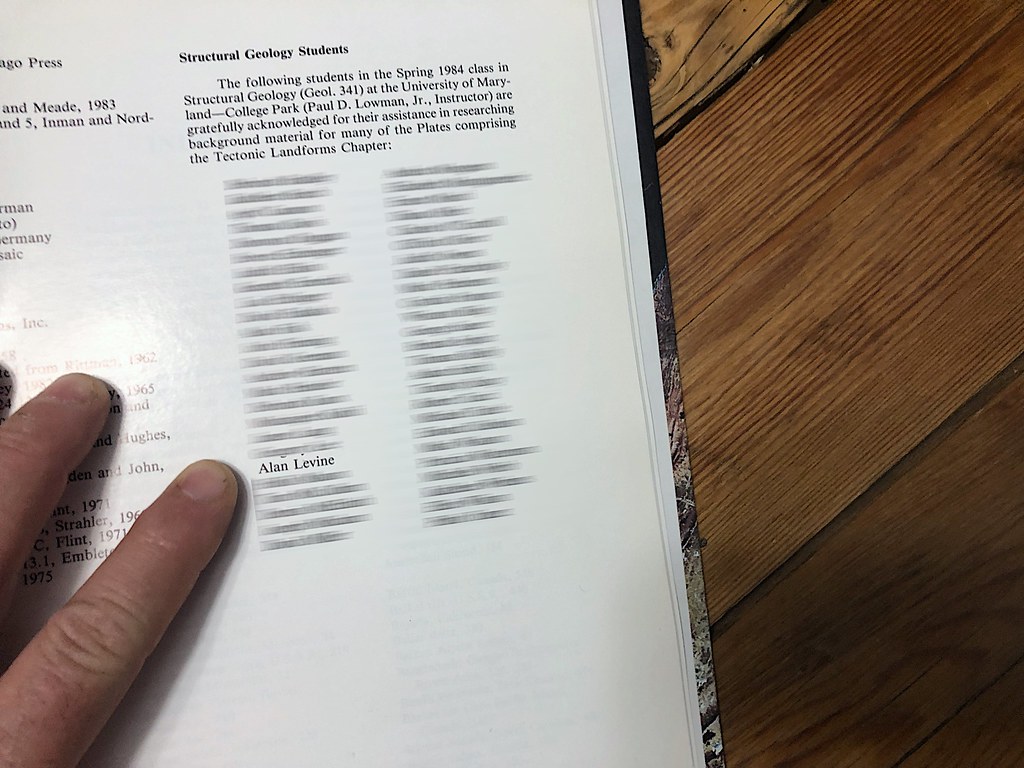

There’s my proof… well actually is there on page 707 (bottom of appendix in online version, in the photo below I blurred other student names for privacy sake).

The section above our names reads:

The following students in the Spring 1984 class in Structural Geology (Geol. 341) at the University of Maryland-College Park (Paul D. Lowman, Jr., Instructor) are gratefully acknowledged for their assistance in researching background material for many of the Plates comprising the Tectonic Landforms Chapter:

So this may not strictly be “Open Pedagogy” as the published book is not openly licensed (name the licenses available in 1984?) and also it was not exactly like writing a whole chapter, I contributed some research notes that likely the expert authors knew.

But that is not the point. Dr. Lowman had, from who knows where, created a project that was not just an assignment, but some real research that was a contribution for a larger work. The effect on me as a student is immeasurable- this is the only thing I remember from not only this one class, but all the classes I took that semester.

So What?

I am not writing this to make some early claim about open pedagogy. It more affirms that I experienced not only these two, but many experiences of effective pedagogy as a student (heck I never knew it was a word). That is what great teachers, memorable ones, have always done.

Or it is just as likely, for me in my second Write 6×6 post, that I am just using it as an excuse to do some Alan-based storytelling from the Proto-Archaic Pre-Internet Era.

Featured Image: A mashup of my own photo, In This Book flickr photo by cogdogblog shared into the public domain using Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication (CC0) with public domain Free Clip Art image 1980s Era Logo by j4p4n plus a screenshot of a portion of the Wikipedia page for Non-Euclidean Geometry — that might make this end up as CC BY-SA?

Comments